On a foggy morning in June 2021, I left my Durham, North Carolina, home to travel two and a half hours to rural Whiteville, North Carolina, population 5,000-ish. I headed there to meet some of the town’s newest, albeit temporary, residents: 200 Haitian migrants employed as blueberry pickers.

These farm workers put food on our tables – and on family tables back in Haiti. But they’re a less visible work force in our food supply chain, toiling largely out of sight on farms in places like Columbus county, with its miles of fields. They are doubly invisible among US guest workers, who overwhelmingly hail from Mexico.

But Haitian migrants also come to the US and locations across the hemisphere to work in food production or other service industries. Their numbers have increased after the devastating 2010 earthquake, and many have been able to use temporary protected status (TPS) to stay and work in the US due to conditions that make it hard to return home.

Others brave unsafe border crossings into the Dominican Republic’s sugarcane fields for abusively low wages. Some board rickety boats to voyage into Turks and Caicos’s shark-filled waters to serve tourists in luxury resorts. Many endure human trafficking into Maryland to pick tomatoes or risk getting whipped by border patrol agents as they walk across the arid US-Mexico border. And as anthropologists Vincent Joos and Laura Wagner once pointed out, there’s a good chance your Thanksgiving turkey was processed by Haitian workers in North Carolina.

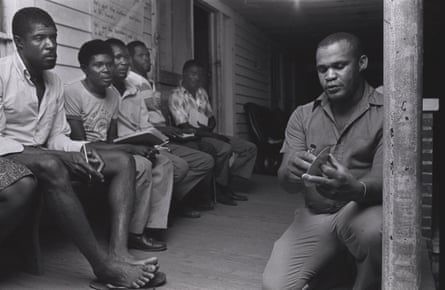

During the pandemic’s peak, I volunteered to do Kreyòl translation so the Whiteville workers could get what was then a scarce commodity, the Covid vaccine. Because non-Spanish-speaking migrant farm workers were often an afterthought (then and now), there were few Covid-specific health resources in the creole language Haitians speak.

I’m a scholar of Haitian migration, and much of my writing and research is inspired by my own family history. My paternal grandmother arrived in the US in 1963, and my father joined her in New York a few years later. I grew up knowing about urban Haitian enclaves all over the US, from Queens to Miami’s Little Haiti. However, few people have documented or even know about Haitian life in the rural US, especially in the south.

Acting as an intermediary between English-speaking nurses and the Haitian migrants, I saw a different part of the Haitian diaspora in small-town America. By now, most of us have heard that thousands of Haitians have migrated to Springfield, Ohio, to escape volatility at home. In Springfield, they boosted an ailing midwestern factory sector only to become targets of racist rhetoric from the Trump-Vance ticket and others.

It’s become popular to spread false narratives about Haitians, to deride our community as one of criminals and resource vampires. Those unfair charges ignore the history of how western powers plundered Haiti, undermined its existence and fostered systemic crisis.

Haiti’s role in world food systems dates to the 1700s when French colonizers called it the “Pearl of the Antilles”. During the transatlantic slave trade, it ranked among the world’s top sugar and coffee producers. When the Haitian Revolution banned slavery on the island and its leaders declared their independence, Napoleon Bonaparte obsessed over the loss of his empire’s crown jewel. France later forced the young country to reimburse former enslavers for losing their once-captive work force – an indemnity of 150m francs with added interest over time. For decades, the US and other countries refused to recognize Haiti, the world’s first independent Black nation. And we wonder why Haiti is the poorest country in the hemisphere, after centuries of extraction, a Wall Street-fomented US occupation and a succession of coup d’états.

The workers I met in Whiteville were far from “takers” or “illegals”. They held H-2A visas that permit approved businesses to hire foreign labor when US workers aren’t available or interested in open jobs. Bruce McLean Jr, an extension agent in Columbus county, believes that anywhere from 20% to 25% of all blueberry pickers in south-eastern North Carolina are Haitian.

The Whiteville Haitians picked blueberries by hand from mid-June to August. Blueberry pickers often make money by the bucket or box; according to the US Department of Labor, the going wage should be 50 cents a pound for seasonal labor, assuming workers actually make that. In October 2023, the labor department fined a Sampson county, North Carolina, farm contractor for stiffing blueberry workers out of their last weeks of wages, taking their passports and even charging them fees to work in the H-2A program.

The six-week season is intense, with long workdays in blistering heat and rain. Beyond the general physical exertion and working in an unfamiliar place, workers are also exposed to pesticides that linger on the berries or soil. They’re sometimes shuttled from farm to farm because it’s “always blueberry season somewhere”. This group of workers would be moving in 10 days, and that made it all the more important to vaccinate them before their next stop.

At Covid’s height, their very status as farm workers put them at high risk. I understood this instantly when I knocked on doors to find a bathroom. One woman allowed me in, and I saw substandard housing in a mildewy old motel. Although the group in Whiteville was working in the open air, they shared cramped housing without appropriate safety measures. Days or weeks of lodging in a room with four twin beds and one shower made privacy and social distancing impossible.

But there was no time to be sick. Relatives back home – in places like L’Estère, known for its luscious rice fields, or La Gonâve island north-west of Port-au-Prince – were sending frequent WhatsApp messages asking for financial help. Cellphones are a lifeline for these workers, connecting them to family or online church services. The likelihood of attending Sunday mass locally was slim without their own transportation. And when you’re a migrant berry picker, there’s almost always more work to do.

The Springfield, Ohio, of North Carolina

Seventy miles away, Haitian labor flocked to Mount Olive, an agricultural town known for its pickle company of the same name (and also being the site of a long struggle to organize farm workers for better conditions).

There are no good estimates of how many Haitians have come to Mount Olive. Advocates usually say that about 3,000 to 4,000 Haitians arrived after 2010. Pastor Occene Louis of the First Haitian Baptist church thinks that as many as 10,000 have passed through Mount Olive, coming from Brazil or Chile and then moving to other North Carolina cities. A large enough number stayed in Mount Olive that he said the town doesn’t have enough housing; he knows of households with a dozen residents.

Perhaps the US census sheds the best, though still imperfect, light on Mount Olive migration patterns. In 2000, Black residents of Mount Olive made up 12% of the population. Twenty years later, they constituted 49%.

The town’s now-deceased longtime mayor, Roy McDonald, acknowledged the essential role that Haitians play in the local economy in the film Home Away from Haiti.

He said: “We need ’em worse than they need us, as most of the locals will simply not do that work. It is very hard work. It is dirty work. Again, if they went away, a lot of our major production facilities would have to struggle.”

In poultry processing, Haitians drive delivery trucks, butcher carcasses and trim skin from the meat. It’s not only dirty work; it’s dangerous. A town resident told me one laborer lost his hand.

This “beneficial Haitian invasion” met with various responses. Some longstanding residents were “big-hearted” and welcoming. Others sold their homes and left.

Former resident Paulette Bekolo lived in Mount Olive for several years starting in 2011 and saw the growing pains. She found herself advocating for basic rights for Haitian and other workers. Bekolo met with some poultry plants’ human resources departments because “the working conditions were awful. Some of them were denied basic toilet breaks. They were humiliated peeing on them[selves].” She organized classes in English as a second language, first aid and immigrant rights to help her compatriots fit in.

Haitians have left an undeniable mark on the town. Haitian supermarkets have popped up and sell lalo (jute leaves) for stew. While attending a church service was largely out of reach for the Whiteville seasonal workers, Mount Olive’s more established community has seven churches vying for their attendance and souls. Some offer services and Bible study in Kreyòl.

In Whiteville, the only business near the moldy motel where Haitians resided was a farm advertising its strawberries, likely picked by other migrants. Women cooked over open fires in a parking lot – a sign of just how transient this migrant community was. The chef there asked me, “Cherie, ki sa ou vle?” (Honey, what do you want?) as she grabbed the vegetable oil.

In Mount Olive, I was served a kitchen-prepared plate of macaroni, rice, beans and meat, and was invited to sit with church congregants. The smells of simmering onions and vegetables in both towns reminded me of my grandmother’s food. I was at home in another part of the country, being fed by Haitian women who help feed us all.

9 months ago

9 months ago

(200 x 200 px).png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·